The World Lighthouse Hub

A17: The Greeks

A detailed study of Greek mariners and their use of navigational aids is given in the downloadable paper J03 Greek Lightstructures.

There is evidence of human agricultural activity on mainland Greece at Thessaly and at Knossus (or Cnossus) on Crete around the early 7th millennium BC, though we should remember that earlier sites may yet be discovered on mainland Greece. The settlement of the Cyclades islands of the Aegean took place in the late 6th and early 5th millennia. From these statements, it is clear that humans were using the seas for travel from an early time. For example, the exploitation of obsidian from the island of Melos is thought to have taken place before it was settled. Because they were limited to economic records, Linear A and B scripts contain no contemporary statements of history of the Minoan or Mycenaean cultures, and a clear idea of them remains elusive. It relies heavily on archaeological evidence and interpretations of the earliest Greek myths and Homeric epics, which were necessarily written many years later.

The earliest civilisation of significance in the Mediterranean as a whole occurred on the island of Crete around 3,000 BC at Knossus and is known as Minoan. Although the great palace of Knossus was built around 1,900 BC, it was constructed on top of many earlier layers of settlement. A separate culture developed independently in Egypt also around 3,000 BC. The Cycladic period refers to a later culture in the region of the Aegean and Helladic to the mainland culture of the time.

Before 3,000 BC, traditional archaeology regards the entire region as being in the Stone Age, a period of very modest technology without the benefits achievable from the possession of metal tools. (We have discussed the advantage gained in shipbuilding by the Phoenicians with their advantage in metallurgy and, in particular, of iron tools and nails.) There is evidence for the building of monumental buildings and fortifications in the so-called pre-palatial period on Crete of 3,300 – 1,000 BC, but these are always attributable to buildings of high significance.

In numerous publications, Heyerdahl has proposed the export of a Mediterranean culture across the Atlantic Ocean, based upon the construction of rafts made from papyrus reeds in the period before 3,000 BC. There is no reason to disagree with this hypothesis, except to say that such craft relied essentially on being carried along by wind and tides and were only crudely navigable. They could not have been used on a significant basis for regular journeys for the purposes of trading across the entire Mediterranean. Additionally, it is hardly likely that the amount of sea travel involved in the use of papyrus rafts merited any kind of navigational aid worthy of description as a lightstructure. Thus, we conclude that before 3,000 BC it is unlikely that sufficient significant activity took place on the sea, and we can disregard the possibility of a culture creating lightstructures before 3,000 BC at the earliest. Seagoing vessels in the Aegean first used sail around 2,000 BC. Trading by sea between the Minoan and Egyptian peoples between 2,000 BC and 1,750 BC is supported by finds of lapis lazuli from Mesopotamia, gold, ivory and alabaster from Egypt, ostrich eggs from Egypt and Libya and amber from the north [35].

The geography of Greece played a big part in determining its early history because the southern mainland is essentially an island, joined to the northern mainland only by a small stretch of land centred on Corinth. Thus, the Minoan culture flourished unchallenged for about 1,400 years from 3,000 BC until 1,600 BC. Over four centuries, a new power arose at Mycenae in the southern mainland around 2,000 BC and was in significant competition with the Minoans by 1,600 BC. A struggle for power between the two was inevitable and by 1,450 BC the Minoan civilisation was in serious decline, replaced by the people of Mycenae.

There was obviously significant interaction between Knossus and Mycenae, separated by over 200 km of sea, and it is clear that travel across such distances was common. Whilst much of the distance could have been covered by navigation along the coast from one point of known land to the next, there was also a portion of voyage across open sea. It is also clear that such distance could not have been covered in one period of daylight and that the ships either used celestial navigation at night or put into ports along the route.

By 1,450 BC, the Mycenaean sphere of influence extended across southern and eastern Greece, the Aegean islands, the western shores of Asia Minor and Cyprus. Regular embassies were exchanged with Egypt, Mesopotamia, Anatolia and the city-states of Syria and Palestine. Trading was commonplace throughout the eastern Mediterranean. By 1,300 BC, Mycenae was by far the richest place in the north Mediterranean lands and the king was overlord to much of Greece. Despite all this activity, we have no evidence that lightstructures were ever created or used during this very early period of sea travel.

The origins of the Hellenic people are thought to have been migrations or invasions from the lands to the north of Greece to occupy the mainland of Greece around 2,000 BC. Some scholars believe that the final invasion by the Dorians around 1,200 BC brought about the destruction of the Mycenaean civilisation and the mass migrations of people expelled from regions surrounding the Aegean - the Invasions of the Sea People. Others maintain that the Dorian invasion did not take place and that the Sea Peoples were in fact mercenaries from Sardinia. These conclusions remain the subject of debate today. Whatever, the cause, the effect was the destruction across an enormous area of dozens of major cities, including Mycenae and its civilisation, in a narrow time-window around 1,200 BC. The culture that is today referred to as the “Western Culture” is a direct derivative of the blending of the Hellenic culture with the remnants of the Eastern Roman Empire that took place around 300 AD.

By this time, a competing culture had developed based in Troy, or Ilium, as it was also called. The resulting Trojan wars resulted in great upheaval from which the Mycenaean civilisation did not recover, such that much unrest followed in 1,250 BC. It is thought that this contributed to the invasions of the Sea Peoples to whom we have referred earlier, and this, in turn, slowed the development of other civilisations in the region, notably the Phoenicians, for a further 200 years. Others suggest that a series of earthquakes destabilised the entire region. Whatever the causes, Greece entered a dark period that lasted from around 1,200 to 800 BC.

The Phoenicians were known to be trading with the people of Crete by 900 BC and were firmly in the process of building established sea routes across the Aegean by 800 BC. The Helladic civilisation was recovering by 800 BC, such that by the time of Homer in 750 BC, its people had not only absorbed the alphabet invented by the Phoenicians, but had modified and improved it, and were starting to use it for the history and philosophy we read today. Our modern alphabet is a direct derivation of the original Phoenician, through the mediacy of the Helladic culture that is often described as Greek.

The period between 750 and 550 BC saw a great new phase of expansion and settlement by the Greeks, regaining all the territories that had once been part of the Mycenaean culture as well as expanding into southern Italy, Sicily and the coastal regions of the black Sea. Trade was a significant, if not the most important factor in this expansion and the Greeks competed with the Phoenicians for the lion’s share of the business. Lightstructures are associated with creative, positive environments, and if they had not been built before, they were surely in use during this period. Literature was now established in the culture, yet we have no evidence of any lightstructures.

The greatest sources of the ancient history of these times are the Iliad and the Odyssey, both attributed to Homer around 750 BC, but both created before modern writing styles had matured. It is easy to dismiss the old legends as valueless from a historical viewpoint. Thus, Witney [19] writes

“Some scholars have suggested that the myth of the Cyclops, the giant with a solitary eye dead-centre in his forehead, may have originated in the primitives fear of lighthouses built, perhaps in the Mediterranean by some advance civilisation whose existence has been obliterated by time.”

The knowledge that the ideas of navigational aids existed in the minds of the people of ancient times tells us that there is a strong possibility that such things existed, irrespective of the fanciful ways in which the stories are portrayed. Legends should be considered carefully for the elements of truths and culture contained within. Thus, we can see that it is very likely that the concept of lightstructures for navigational aids could have been commonplace in the culture of the ancient Greeks at the time of Homer in 750 BC.

Beaver [21] wrote:

“Another legend attributes the first lighted sea beacon to Hercules who, having donned the shirt of Nessus, in his agony tore the flesh from his own body. Unable to stand the pain, he built himself a funeral pyre by the sea and threw himself upon it. At Thassos, Smyrna and in Italy he was known as the saviour of voyagers”

Still another story [24] tells how Nauplius, an argonaut, displayed fires in a wrong position at Caphareus in Euboea, to represent the lights of vessels, and thus misled and wrecked a Greek fleet returning from Troy. This point is also interesting in that it identifies the dark side of mankind that was later imitated by the people known as wreckers who carried out similar cruel deeds in England and France in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Perhaps being overcritical in his assessments, Stevenson [24] does not accept that the earliest texts actually refer to the idea of lighthouses, insisting that misinterpretations have occurred in translation. He writes:

In the 18th century, the study of mythology was a necessary part of a liberal education and antiquaries, when interpreting the past, did not hesitate to draw freely on their imagination when facts were not obvious. To the less credulous, the Cyclops, the monstrous cannibals each with one huge eye, who, it was believed, dwelt in Sicily or in the depths of Etna where they manufactured lightning and thunder-bolts for Zeus, were fanciful allusions to actual lighthouses.

Specifically writing about Homer, Stevenson concludes negatively:

The suggestion that Homer alluded to lighthouses in both the Iliad and the Odyssey appeared first during the 19th century but examination of the Greek texts shows that it cannot be substantiated. The passage referred to most often in this connection is one in Book XIX of the Iliad which has been interpreted as describing Achilles' polished shield as being so bright that its reflection resembled the flash of a beacon fire or lighthouse. The translation from the Greek text is as follows: 'As when from the sea, sailors see the light of a fire that burns high on the mountains in a lonely steading, while, against their will, the breezes carry them over the fishy sea away from their own folk; so, from Achilles' shield, bright and beautifully engraved, the light streamed to heaven.' Other translations of the passage, such as George Chapman's robust version of 1616, offer no support to the idea that Homer referred to lighthouses, though the following lines by Alexander Pope, who sought about 1720 to reproduce Homer's masterpiece in a poem in English and was unfettered by a call for an exact translation, may have been responsible unintentionally for the suggestion of a lighthouse:

'So to night-wandering sailors, pale with fears,

Wide o'er the wat'ry waste a light appears,

Which on the far-seen mountain blazing high,

Streams from some lonely watch-tower to the sky.'

Homer’s works were essentially epic poems, which were passed down through subsequent generations, very much through performance in song, recitation and dramatic art. However, it is believed that they do represent a good record of the history, which, at the time of Homer, was already 500 years old. Unlike modern history, he could not base it on things he read in books. Furthermore, our consensus is that the concepts of lightstructures actually did exist even if they were romanticised according to the styles in which history was recorded at that time. The modern ideas of precise, critical appraisal did not exist and the style was much looser in fact and very much one of recounting myths and legends. The Greeks never doubted their own history and believed that Homer’s heroes were real people, supported by the fact that the places he talked about were identifiable. [7].

Driven by the need for trade and raw materials, especially metals, the Greeks became outward looking from about 750 onwards, identifying locations for new colonies around the Mediterranean and Black Seas. So began a period during which they created a large number of so-called ‘city-states’. Their first colony of significance was Cumae near present-day Naples, founded as an outpost to acquire sources of tin. Other colonies followed, and the development of a strong Greek presence in northern Italy, Corsica and Sicily was a strong catalyst for the transmission of the Greek culture to the Etruscans and the emergent Roman State. However, in many aspects, they were unable to compete with the Phoenicians who were the most powerful influence at sea and, besides, Greek trading was largely conducted by land to the north and east. The earliest events of Greek exploration are thought to be the 7th century voyage of Aristeas of Prokonessos to the northern shores of the Black Sea and eastwards to the Hindu Kush.

The period from the time of Homer to the defeat of the Persians at Salamis is called the period of Archaic Greece, 700 BC to 480 BC. This period of history is characterised by a pattern of civilisation known as city-states. (We have already seen that the Phoenicians adopted a similar style of settlement). Homer’s Iliad tells how Greeks from many city-states - among them, Sparta, Athens, Thebes, and Argos - joined forces to fight their common foe, Troy in Asia Minor. Greek city-states formed an alliance when the power of Persia threatened them but ancient Greece never became a nation. An ancient Greek’s loyalty was only to his city and the cities were small: Athens was probably the only Greek city-state with more than 20,000 citizens.

Often, a single plain contained several city-states, each surrounding its acropolis, or citadel. Sometimes separated by barriers of sea and mountain, by local pride and jealousy, the various independent city-states never conceived the idea of uniting the Greek-speaking world into a single political unit. Many influences made for unity - a common language, a common religion, a common literature, similar customs, the religious leagues and festivals such as the Olympic Games - but even in time of foreign invasion it was difficult to induce the cities to act together.

From 480 BC until 323 BC is known as the Classical Age of Greek history. The transition from the Archaic period was largely initiated by the continuing conflicts with the Assyrian empire and its expansionist policy under Darius, King of the Persians. After annexing many of the Greek colonies in Asia minor he attacked mainland Greece, but was defeated at Marathon in 490 BC. The Athenians built up their navy and a series of conflicts with the successors to Darius, of whom Xerxes is perhaps the bet known, took place over several decades that followed. Many successes and reversals occurred on both sides and the struggle for ultimate power was settled only when Macedonian power arose in 357 BC under Philip of Macedon, and then, more significantly, under his son Alexander.

By 323 BC Alexander the Great had achieved supreme dominance from Egypt to Pakistan and this was only broken by his death in 323 BC. There was no instant evaporation of Alexander’s empire, but those regional powers that had been constrained in Alexander’s grip for so long, breathed a big sigh of relief. A new age called the Hellenistic Period, 323 BC to 30 BC, began with a huge release of energy, and over the years that followed a large number of new works commenced on a truly grand scale, not least of which was the Pharos of Alexandria.

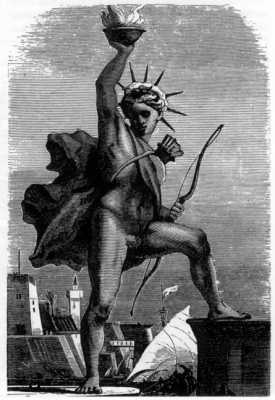

Fig. A17.1: The Colossus of Rhodes

The Greeks built a wonderful construction known as the Colossus of Rhodes around 280 BC, at much the same time as the Pharos. A bronze figure of Apollo, over 30 metres high, was made by the sculptor Chares and stood at the entrance to the harbour of Rhodes. The statue is supposed to have lasted 56 years and was destroyed by an earthquake about 224 BC. A traveller in the 1st century AD who observed the broken limbs reported that it was strengthened with blocks of stone contained within them. About 700 AD three hundred tons of its metal were sold as scrap and transported to Alexandria. By the 16th century it was being written that “the figure bestrode the harbour entrance so that ships in full sail could pass between its legs”. Furthermore, navigation lights were supposedly kept burning in its eyes and it held a flaming beacon in one hand. These stories are considered to be unlikely, for just how these lights were maintained is a mystery. Hague writes:

“It has been claimed that the slightly hollow battlemented crowns on the heads of some classical statues of goddesses served as cressets or fire-baskets, but the evidence is unsatisfactory, being based on statuette copies of the originals whose size and provenance is unknown. Furthermore, if the statuettes are accurate, the jaunty angle at which the crowns are worn would have resulted in the discharge of the oil or fat down the neck of the deity.”

The Colossus of Rhodes

Stevenson [24] dismisses the Colossus as a lighthouse, but many pharologists do include it in their lists of lightstructures. This structure will remain on our list of uncertainties, but is in any case unlikely to be a candidate for ‘first lightstructure’.

Thus, it is in the period prior to the pivotal year of 323 BC that we must look for evidence of any lighthouses of the pre-Pharos era. If the Phoenicians had built lighthouses, it would surely have been at some point during the period from the establishment of Carthage in 814 BC to 323 BC. (Remember that Carthage was regarded as being their first permanent colony.) We have already shown that there is virtually no firm evidence for this. We might ask that, if the Greeks had begun to build lighthouses during this early period, surely the Phoenicians would have realised how powerful the idea could be to them and would have copied it? If the Phoenicians had built a lightstructure at Carthage, then why did hey not build many others? Yet, the Greeks are not regarded as competing in any way with the mastery of the seas displayed by the Phoenicians. That is not to say that they did not build some basic lighthouses in their own ports and that is what we need to investigate.